HTTP Operational Model and Client/Server Communication

2012-12-14 11:57

507 查看

he Hypertext Transfer Protocol is the application-layer protocol that implements the World Wide Web. While the Web itself has many different facets, HTTP is only concerned with one basic function: the transfer of hypertext documents

and other files from Web servers to Web clients. In terms of actual communication, clients are chiefly concerned with making requests to servers, which respond to those requests.

Thus, even though HTTP includes a lot of functionality to meet the needs of clients and servers, when you boil it down, what see is a very simple, client/server, request/response protocol. In this respect, HTTP

more closely resembles a rudimentary protocol like BOOTP or

ARP than it does other application-layer protocols like

FTP and

SMTP, which all involve multiple communication steps and command/reply

sequences.

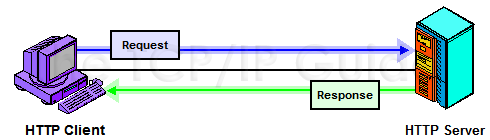

Basic HTTP Client/Server Communication

In its simplest form, the operation of HTTP involves only an HTTP client, usually a

Web browser on a client machine, and an HTTP server, more commonly known as a

Web server. After a TCP connection is created, the two steps in communication are as follows:

Client Request: The HTTP client sends a request message formatted according to the rules of the HTTP standard—an

HTTP Request. This message specifies the resource that the client wishes to retrieve, or includes information to be provided to the server.

Server Response: The server reads and interprets the request. It takes action relevant to the request and creates an

HTTP Response message, which it sends back to the client. The response message indicates whether the request was successful, and may also contain the content of the resource that the client requested, if appropriate.

Figure 315: HTTP Client/Server Communication

In HTTP/1.0, each TCP connection involves only one such exchange, as shown in

Figure 315; in HTTP/1.1, multiple exchanges are possible,

as we'll see in the next topic. Note also that the server may

in some cases respond with one or preliminary responses prior to sending the full response. This may occur if the server sends a preliminary response using the “100 Continue” status code prior to the “real” reply.

See the topic on HTTP status codes for more information.

ntermediaries and The HTTP Request/Response Chain

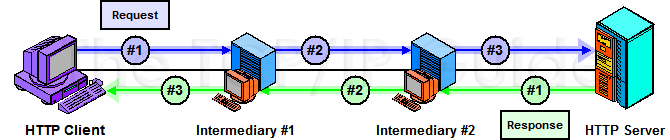

The simple request/response pair between a client and server becomes more complex when

intermediaries are placed in the virtual communication path between the client and server. These are devices such as

proxies, gateways or tunnels that are used to improve performance, provide security or perform other necessary functions for particular clients or servers. Proxies are particularly commonly used on the Web, because they can greatly

improve response time for groups of related client computers.

When an intermediary is involved in HTTP communication, it acts as a “middleman”. Rather than the client speaking directly to the server and vice-versa, they each talk to the intermediary. This allows the intermediary

to perform functions such as caching, translation, aggregation, or encapsulation. For example, consider an exchange through a single intermediary device. The two-step communication process above would become four steps:

Client Request: The HTTP client sends a request message to the intermediary device.

Intermediary Request: The intermediary processes the request, making changes to it if necessary. It then forwards the request to the actual server.

Server Response: The server reads and interprets the request, takes appropriate action and then sends a response. Since it received its request from the intermediary, its reply goes back to the

intermediary.

Intermediary Response: The intermediary processes the request, again possibly making changes, and then forwards it back to the client.

As you can see, the intermediary acts as if it were a server from the client's perspective, and as a client from the server's viewpoint. Many intermediaries are designed to be able to “intercept” a variety of

TCP/IP protocols, by “posing” as the server to a client and the client to a server. Most protocols are unaware of the existence of the interposition of an intermediary in this fashion. HTTP, however, includes special support for certain intermediaries such

as proxy servers, providing headers that control how intermediaries handle HTTP requests

and replies.

It is possible for two or more intermediaries to be linked together between the client and server. For example, the client might send a request to intermediary 1, which then forwards to intermediary 2, which then

talks to the server; see Figure 316. The process is

reversed for the reply. The HTTP standard uses the phrase request/response chain to refer collectively to the entire set of devices involved in an HTTP message exchange.

Figure 316: HTTP Request/Response Chain Using Intermediaries

The Impact of Caching on HTTP Communication

The normal HTTP communication model is changed through the application of

caching to client requests. Caching is employed by various devices on the Web to store recently-retrieved resources so they can be quickly supplied in reply to a request. The client itself will cache recently-accessed Web documents so that if the user

asks for them again they can be displayed without even making a request to a server. If a request is in fact required, any intermediary device can satisfy a request for a file if the file is in its cache.

When a cache is used, the device that has the cached resource requested returns it directly, “short-circuiting” the normal HTTP communication process. In the example above, if intermediary 1 has the file the client

needs, it will supply it back to the client directly, and intermediary 2 and the real Web server that the client was trying to reach originally will not even be aware that a request was ever made;

the topic on HTTP caching discusses the subject in much more detail.

Note:

Most requests for Web resources are made using HTTP URLs

based on a Domain Name System (DNS) host name. The first step in satisfying such requests

is to resolve the DNS domain name into an IP address, but this process

is separate from the HTTP communication itself.

and other files from Web servers to Web clients. In terms of actual communication, clients are chiefly concerned with making requests to servers, which respond to those requests.

Thus, even though HTTP includes a lot of functionality to meet the needs of clients and servers, when you boil it down, what see is a very simple, client/server, request/response protocol. In this respect, HTTP

more closely resembles a rudimentary protocol like BOOTP or

ARP than it does other application-layer protocols like

FTP and

SMTP, which all involve multiple communication steps and command/reply

sequences.

Basic HTTP Client/Server Communication

In its simplest form, the operation of HTTP involves only an HTTP client, usually a

Web browser on a client machine, and an HTTP server, more commonly known as a

Web server. After a TCP connection is created, the two steps in communication are as follows:

Client Request: The HTTP client sends a request message formatted according to the rules of the HTTP standard—an

HTTP Request. This message specifies the resource that the client wishes to retrieve, or includes information to be provided to the server.

Server Response: The server reads and interprets the request. It takes action relevant to the request and creates an

HTTP Response message, which it sends back to the client. The response message indicates whether the request was successful, and may also contain the content of the resource that the client requested, if appropriate.

|

Figure 315; in HTTP/1.1, multiple exchanges are possible,

as we'll see in the next topic. Note also that the server may

in some cases respond with one or preliminary responses prior to sending the full response. This may occur if the server sends a preliminary response using the “100 Continue” status code prior to the “real” reply.

See the topic on HTTP status codes for more information.

Key Concept: HTTP is a client/server-oriented, request/reply protocol. Basic communication consists of an HTTP Request message sent by an HTTP client to an HTTP server, which returns an HTTP Response message back to the client. |

The simple request/response pair between a client and server becomes more complex when

intermediaries are placed in the virtual communication path between the client and server. These are devices such as

proxies, gateways or tunnels that are used to improve performance, provide security or perform other necessary functions for particular clients or servers. Proxies are particularly commonly used on the Web, because they can greatly

improve response time for groups of related client computers.

When an intermediary is involved in HTTP communication, it acts as a “middleman”. Rather than the client speaking directly to the server and vice-versa, they each talk to the intermediary. This allows the intermediary

to perform functions such as caching, translation, aggregation, or encapsulation. For example, consider an exchange through a single intermediary device. The two-step communication process above would become four steps:

Client Request: The HTTP client sends a request message to the intermediary device.

Intermediary Request: The intermediary processes the request, making changes to it if necessary. It then forwards the request to the actual server.

Server Response: The server reads and interprets the request, takes appropriate action and then sends a response. Since it received its request from the intermediary, its reply goes back to the

intermediary.

Intermediary Response: The intermediary processes the request, again possibly making changes, and then forwards it back to the client.

As you can see, the intermediary acts as if it were a server from the client's perspective, and as a client from the server's viewpoint. Many intermediaries are designed to be able to “intercept” a variety of

TCP/IP protocols, by “posing” as the server to a client and the client to a server. Most protocols are unaware of the existence of the interposition of an intermediary in this fashion. HTTP, however, includes special support for certain intermediaries such

as proxy servers, providing headers that control how intermediaries handle HTTP requests

and replies.

It is possible for two or more intermediaries to be linked together between the client and server. For example, the client might send a request to intermediary 1, which then forwards to intermediary 2, which then

talks to the server; see Figure 316. The process is

reversed for the reply. The HTTP standard uses the phrase request/response chain to refer collectively to the entire set of devices involved in an HTTP message exchange.

|

Key Concept: The simple client/server operational model of HTTP is complicated when intermediary devices such as proxies, tunnels or gateways are inserted in the communication path between the HTTP client and server. HTTP/1.1 is specifically designed with features to support the efficient conveyance of requests and responses through a series of steps from the client through the intermediaries to the server, and back again. The entire set of devices involved in such a communication is called the request/response chain. |

The normal HTTP communication model is changed through the application of

caching to client requests. Caching is employed by various devices on the Web to store recently-retrieved resources so they can be quickly supplied in reply to a request. The client itself will cache recently-accessed Web documents so that if the user

asks for them again they can be displayed without even making a request to a server. If a request is in fact required, any intermediary device can satisfy a request for a file if the file is in its cache.

When a cache is used, the device that has the cached resource requested returns it directly, “short-circuiting” the normal HTTP communication process. In the example above, if intermediary 1 has the file the client

needs, it will supply it back to the client directly, and intermediary 2 and the real Web server that the client was trying to reach originally will not even be aware that a request was ever made;

the topic on HTTP caching discusses the subject in much more detail.

Note:

Most requests for Web resources are made using HTTP URLs

based on a Domain Name System (DNS) host name. The first step in satisfying such requests

is to resolve the DNS domain name into an IP address, but this process

is separate from the HTTP communication itself.

相关文章推荐

- New full duplex HTTP tunnel implementation (client and server)

- java wiki - apache httpserver and httpclient

- using HttpClient and sending json data to RESTful server in adroind

- Simple HTTP Server and Client in Python

- httpserver and client

- Simple HTTP Server and Client in Python

- Simple HTTP Server and Client in Python

- Simple HTTP Server and Client in Python

- Bi-directional communication between Client and Server, using ServerSocket, Socket, DataInputStream

- Web Communication:Server、Client 與 HTTP Protocol

- Simple HTTP Server and Client in Python

- Simple HTTP Server and Client in Python

- Using Spring 4 WebSocket, sockJS and Stomp support to implement two way server client communication

- Simple TCP Socket Client and Server Communication in C Under Linux

- Web.js MVC between client and server

- HTTP 2.0 Client & HTTP 2.0 Server & HTTP 2.0 Proxy

- Csharp:WebClient and WebRequest use http download file

- 安装 NoMachine(NX) client and server

- The client and server cannot communicate, because they do not possess a common algorithm.

- 2Boost之UPD,Client and Server